Beverage production involves processes that require a great deal of cooling and heating energy. For that reason, most manufacturers employ thermal-energy recovery systems that intelligently link their heating and cooling streams. Despite these best efforts, some waste heat is often simply dissipated. Heat pumps can take this energy and use it to generate hot process water, thereby reducing fuel consumption and the associated carbon emissions. Often, it likewise lowers the need for cooling energy. The benefits are even greater if the heat pump runs on electricity generated by in-house photovoltaic or biogas systems. The technology is also a key to the electrification of beverage plants, ultimately enabling the transition to renewable energy sources.

Heat pumps can capture and reuse heat that would otherwise be wasted, further reducing a beverage plant’s energy consumption and carbon emissions. The systems can work centrally at the factory level or be integrated into individual lines or machines. The latter are easy to retrofit.

Heat pumps can be employed to make use of waste heat at three levels: the entire factory, the line and the machine. Krones has extensive experience in all three areas and offers consulting and tools to help find the optimal solution for specific applications. Krones’ teams are also continually working to develop new concepts for deploying heat pumps profitably.

Holistic: central heat pump in the factory

The most cost-effective way to integrate heat pumps is to install centralised heating and cooling systems in combination with energy storage tanks. The waste heat from the factory is collected and brought up to the temperature desired for the hot-water storage tank. This makes it possible for the heat pump to operate independently of individual processes, so it can run more constantly and more efficiently. In addition, the specific investment is lower than it would be to implement it on an individual machine or line. The centralised solution also saves the most carbon emissions. This concept is an excellent choice for greenfield projects, as retrofitting such a system is difficult.

Real-world example

A current example of this centralised approach is the planning of a greenfield brewery in Germany. In its basic design, the brewery will be supplied with heat centrally by way of two heating circuits, each of which is equipped with a heat storage tank. A wood-chip boiler generates high-pressure hot water to between 125 and 145 degrees Celsius for the wort boiler. The rest of the brewery uses low-pressure hot water (95 degrees Celsius), which is provided by a heat pump that takes waste heat from the cooling units and air compressors. Electricity from an on-premises photovoltaic system drives the heat pump.

These measures, together with many others not detailed here, will make it possible to reduce the 500,000-hectolitre brewery’s energy consumption by 30 per cent compared to standard values for the same annual production capacity. It also saves 3,000 tons of carbon emissions each year. And the investment will pay for itself in just five years’ time.

You can find out more about Krones’ sustainability consulting service (including a practical example) in this video from our drinktec forum.

Integrated: Heat pump in the line

Along a production line, cold or heat is often generated in one place that can be used elsewhere in the line. Here, too, heat pumps can be beneficial. Take, as an example, the EquiTherm Coldfill system: cold-filled containers are usually warmed prior to labelling because condensation would otherwise negatively impact the labels. To save energy, the EquiTherm Coldfill moves thermal energy back and forth between the LinaTherm tunnel heater and the Contiflow mixer, where the product is cooled prior to filling. A heat pump draws additional thermal energy from the cooling water coming from the mixer and uses it to generate hot water for the tunnel heater. This further reduces the consumption of heating energy. Less energy is needed for product cooling because the heat pump lowers the temperature of the cooling water. In this way, a typical application can save around 50 per cent of the gas that would otherwise be required for heating. So, it is certainly worth examining one’s production lines for potential to integrate heat pumps.

Island approach: Heat pump in the machine

Heat pumps are especially well suited for use – and relatively easy to retrofit – in all machines that require energy for both cooling and heating. Examples include thermal product treatment, pasteurisation of filled containers and bottle washing.

Focus on heat pumps in the flash pasteuriser

The latest concept from Krones uses heat pumps in the flash pasteuriser, such as the VarioFlash and the VarioAsept. In these systems, the product itself is directly heated and cooled, which means that the characteristics of the product affect heat recovery. As a result, the specific parameters of the individual application will have even greater bearing on any decisions.

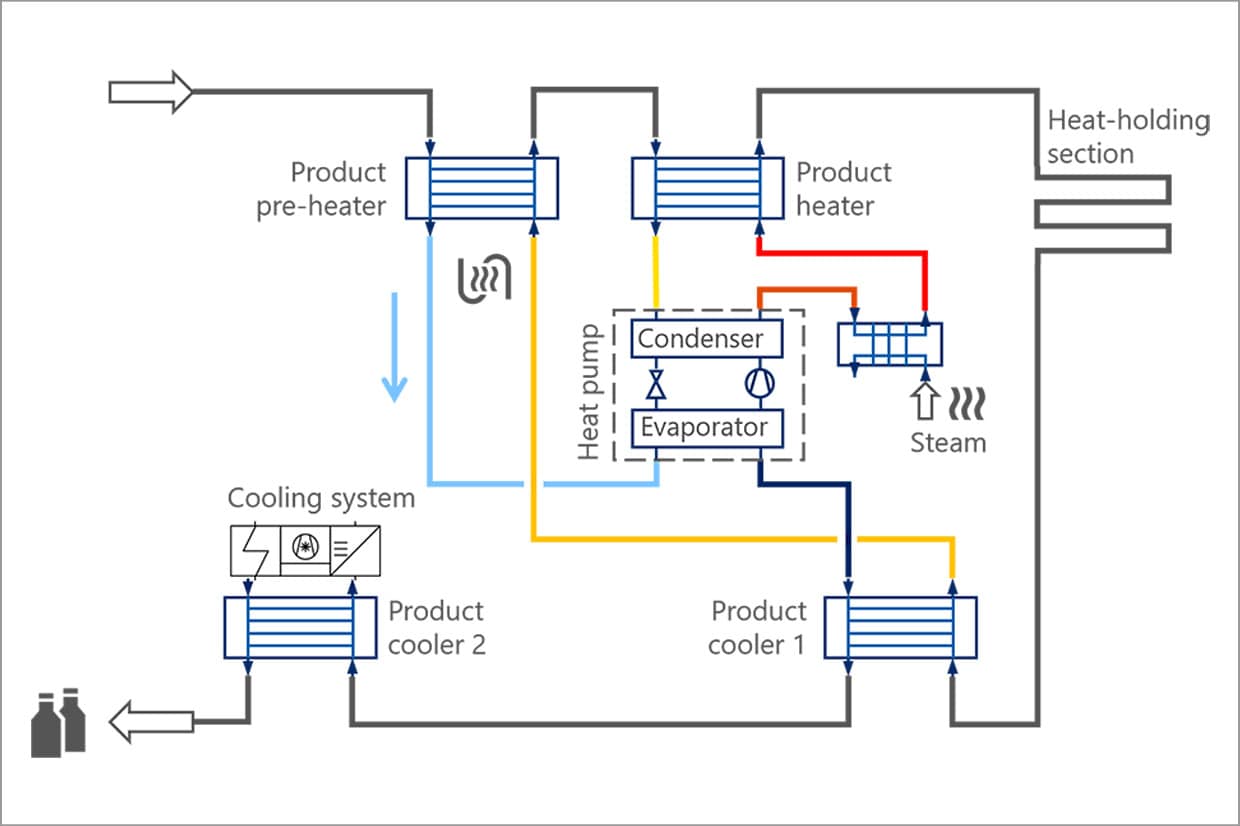

Let’s take a look at the process in detail (see diagram below): The product leaves the mixer and arrives at the flash pasteuriser, where it is pre-heated in a first heat exchanger and then, in a second heat exchanger, brought up to pasteurisation temperature. Following pasteurisation, the product runs through a third heat exchanger for cooling. A second cooling stage brings the product down to the desired filling temperature. The product pre-heater and cooler 1 provide each other with heat and cooling energy by way of an internal water circuit and require no additional outside energy. Only the second cooling stage requires external energy, and the final product heating unit, which runs on steam.

The heat pump is now directly integrated into the internal water circuit. It pulls additional thermal energy from the water returning from the pre-heater and uses it to pre-heat the still-warm water coming back from the final product heater. With just a small amount of additional steam, the water is then hot enough to be fed back into the heating unit. At the same time, the heat pump lowers the temperature of the cooling water. That saves on both steam for heating and energy for cooling.

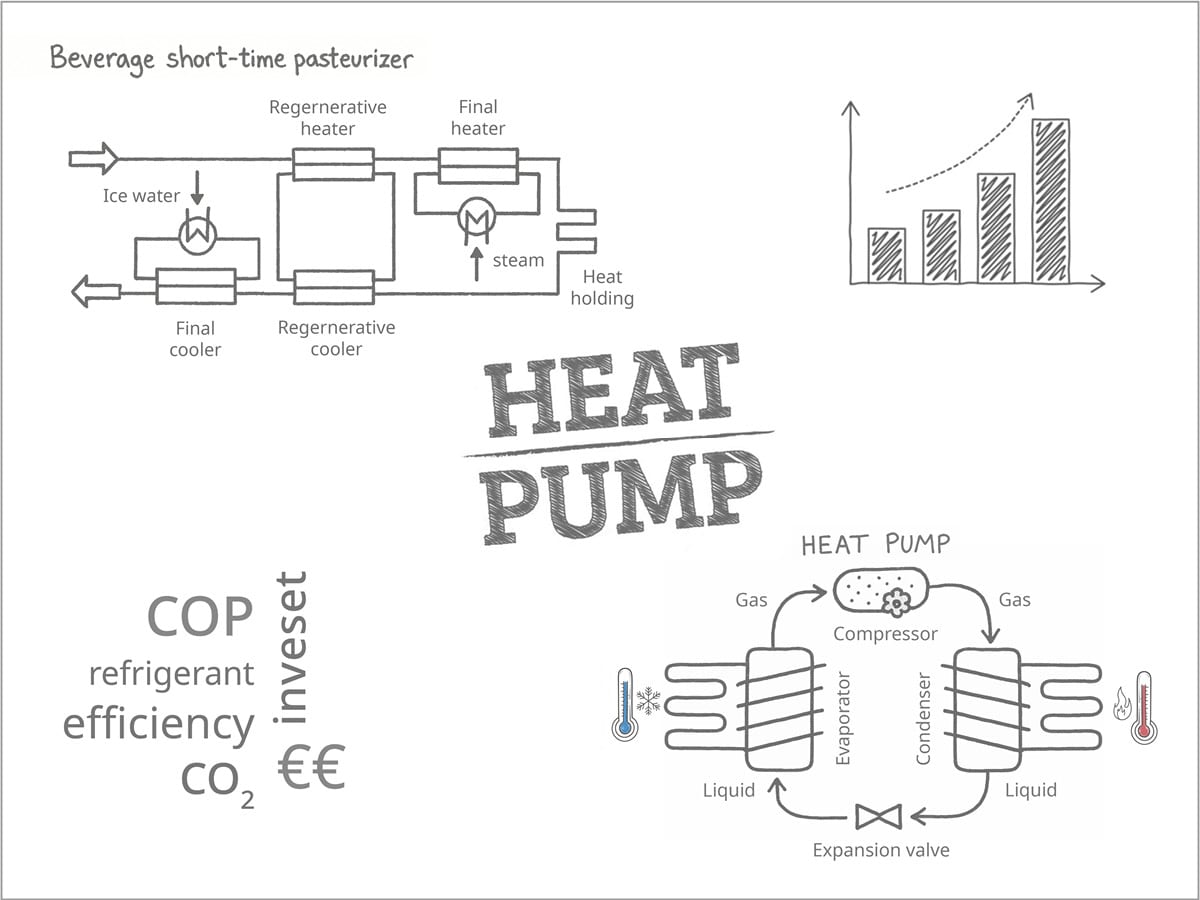

But it doesn’t always necessarily make sense to simply invest in a heat pump. Whether its use would be cost-effective depends on a number of factors, which, in turn, influence each other to some extent (see diagram below). In the example cited above, deploying a heat pump reduces both the amount of gas required for generating steam and the energy consumed for cooling. However, electricity consumption, the initial investment and ongoing operating costs of a heat pump must also be considered. The latter will depend on the application at hand: For instance, the choice of refrigerant for the heat pump will depend on the temperature profile of the process. Additionally, some refrigerants require more stringent safety precautions. So, every application needs to be evaluated in detail, says Dr. Thomas Oehmichen from Krones’ product management team for units and components. He stresses that “Basically, before you invest in a heat pump, you need to first minimise the heat requirements as much as possible.”

Two key factors: Rate of heat recovery and pasteurisation temperature

The key parameter for determining the cost-effectiveness of a heat pump is the coefficient of performance (COP). It is the ratio of the heating or cooling output to the required energy input and will depend heavily on the temperature lift that is to be achieved: The greater the temperature lift, the more electrical energy will be needed by the heat pump – and the less efficient it will be. Put simply, lift is the difference between the hot side and the cool side of the heat pump. In flash pasteurisation, the temperature lift is determined by the process, in particular the inlet temperature of the product that is to be heated, the pasteurisation temperature and the quality of internal heat recovery. The latter indicates how well heat or cold is transferred to the product in the heat exchanger. This much is clear: The better the heat recovery, the greater the temperature lift.

The main factors influencing the heat transfer rate are the type of heat exchanger and the viscosity of the product. Plate heat exchangers transfer more heat than tubular heat exchangers but are only suitable for use with low-viscosity products. At the same time, the more viscous a product, the more poorly heat is transferred in a heat exchanger in general. Thus, a low-viscosity product in a plate heat exchanger will achieve a considerably better rate of heat recovery (typically 90 per cent and higher) than a medium- to high-viscosity product in a tubular heat exchanger (typically around 80 per cent).

A tool for assessing cost-effectiveness

The team at Krones has developed a dedicated tool to quickly assess the cost-effectiveness of a heat pump in light of the many different factors involved. It uses process data, the heat pump’s key data and energy costs to calculate temperature lift, COP, payback period (PBP) in years and carbon emissions.

Using a heat pump for flash pasteurisation – conclusions

Therefore, whether the flash pasteurisation process can benefit from a heat pump will depend heavily on the application at hand and the specific context. The actual cost-effectiveness can be easily estimated in detail using the calculator developed by Krones. What holds true in any case is this: Considering the topic is bound to yield benefits for production operations. Whether refurbishing existing processes and machines or investing in a supplemental heat pump – such a set-up offers significant potential for savings and more sustainable production.

Another case study: Heat pump in the pasteuriser

The new LinaFlex eSync pasteuriser also has the option to integrate a heat pump in its basic configuration. Here, heat consumption has been minimised as recommended: Integrated water circuits transfer thermal energy between paired heating and cooling zones, with insulation preventing external heat loss. If the pasteurisation temperatures vary substantially between different products, additional heat can even be recovered within the pasteurisation zones.

In certain cases, a heat pump can further reduce the remaining energy consumption for pasteurisation, for instance if greater product cooling is required at the discharge end of the pasteuriser. In the additional cooling zone, waste heat is released which the heat pump then uses to generate hot water for the pasteurisation process. Cold water from other processes can often be used for the cooling process itself. As a result, fuel consumption and carbon emissions decrease and the pasteuriser can largely run on electricity. At this year’s drinktec trade fair, Krones presented a case study in which a heat pump with a COP of 2.7 was able to replace 85 per cent of the required heating energy.